What is midfield for?

Can we get a step closer to quantifying what makes a midfielder good by thinking through the theory? We'll see.

Have you ever, and you have no reason to have done, stopped to think about the story of the word 'Eureka's origin? There was a bath, there was Archimedes, there was an insight into measuring the weight and density of objects...

I hadn't, not since I was eight. I just looked it up, and it's really disappointing. It just means "I've found it" [source: Wikipedia]. For whatever reason, the story of Archimedes made it into our language but presumably ancient Greeks were saying that all the time. 'Where did I put my tunic' 'Do you want me to help look for it?' 'Never mind, Eureka'.

All of this is to say that I think I've had a good idea. Alas, the story of its origin is unlikely to get passed down from generation to generation, culture to culture; there was no catchphrase, no baths. There was barely an audible 'oh!'.

As we all know, the point of football is to win. The way you do that is scoring more goals than the opposition. If you want to do some linguistic algebra you could rearrange that formula slightly: it's about scoring more than you concede. I think that most of the fundamental definitions of the sport that you see usually stop there, but there's a key thing they miss.

You have 90 minutes in which to do this.

Now, I know that that will not seem like Archimedean insight, but bear with me for a couple of paragraphs while I try and displace some intellectual water.

The first draft of this newsletter began life the day before the men's Twenty20 cricket World Cup final, a sporting format that offers one of the clearest effects of 'time' as a game mechanic in sport. For those whose lives aren't blessed by wickets and yorkers, teams (of eleven players, like in football) have to split their talents between batting and bowling. In T20s, no bowler can bowl more than four overs (a set of six balls), meaning that, for most of the twenty overs a team is batting for, the specialist batters have half a mind on not getting out. With a team needing at least five bowlers, if the specialist batters get out then the non-specialists have to see out the remaining time.

But then, usually with about two overs of the twenty to go, the calculus flips. Magic happens. There's so little time left to bat that there's no point being cautious, and the risk of swinging for the fences begins to be outweighed by the risk of not swinging for the fences. There's a bit of a parallel of this in football, where teams will go for 'low percentage' balls into the box late in the game, but this tangent is all to bring us to a feature of football without a parallel in T20 cricket. When teams put their foot on the ball.

You don't see this often and there's a strong chance that if you do it's a Pep Guardiola team doing it. Defenders or goalkeepers will just stand there with the ball at their feet, not through lack of options or indecision, not even necessarily to draw out an opposition press, but just because. Because they've realised something: they simply don't need to do anything.

It's radical. It's like The Matrix, seeing the world for what it truly is. We're only 34 minutes into the game, why rush? Let's sit down, make some tea, watch some T20 highlights.

It's also fundamentally different to a sport that otherwise has a lot of similarities to football, and a lot of analytics overlap: basketball. Two sports each with one ball, a goal at both ends, and fluid in-play action. But basketball (the NBA at least, don't ask me about FIBA rules) has a shot clock and backcourt rules, aimed at getting in-possession teams into their opponent's half quickly, and keeping them there.

(As an aside, I think that the biggest single rule-change you could do to increase the 'entertainment' of football matches isn't cracking down on time-wasting or diving at all, but adapting one of those basketball rules. Maybe backcourt violations but for the defensive third or something)

Watching one of those Guardiola games was my Eureka. The world seems to stop. You wonder why anybody bothers to move the ball up-field quickly at all. There's still ten minutes to half-time, you could watch the last three minutes of the (50-over) men's 2019 Cricket World Cup highlights three times over (if your life isn't already blessed by cricket, this would be a fantastic and if bewildering introduction).

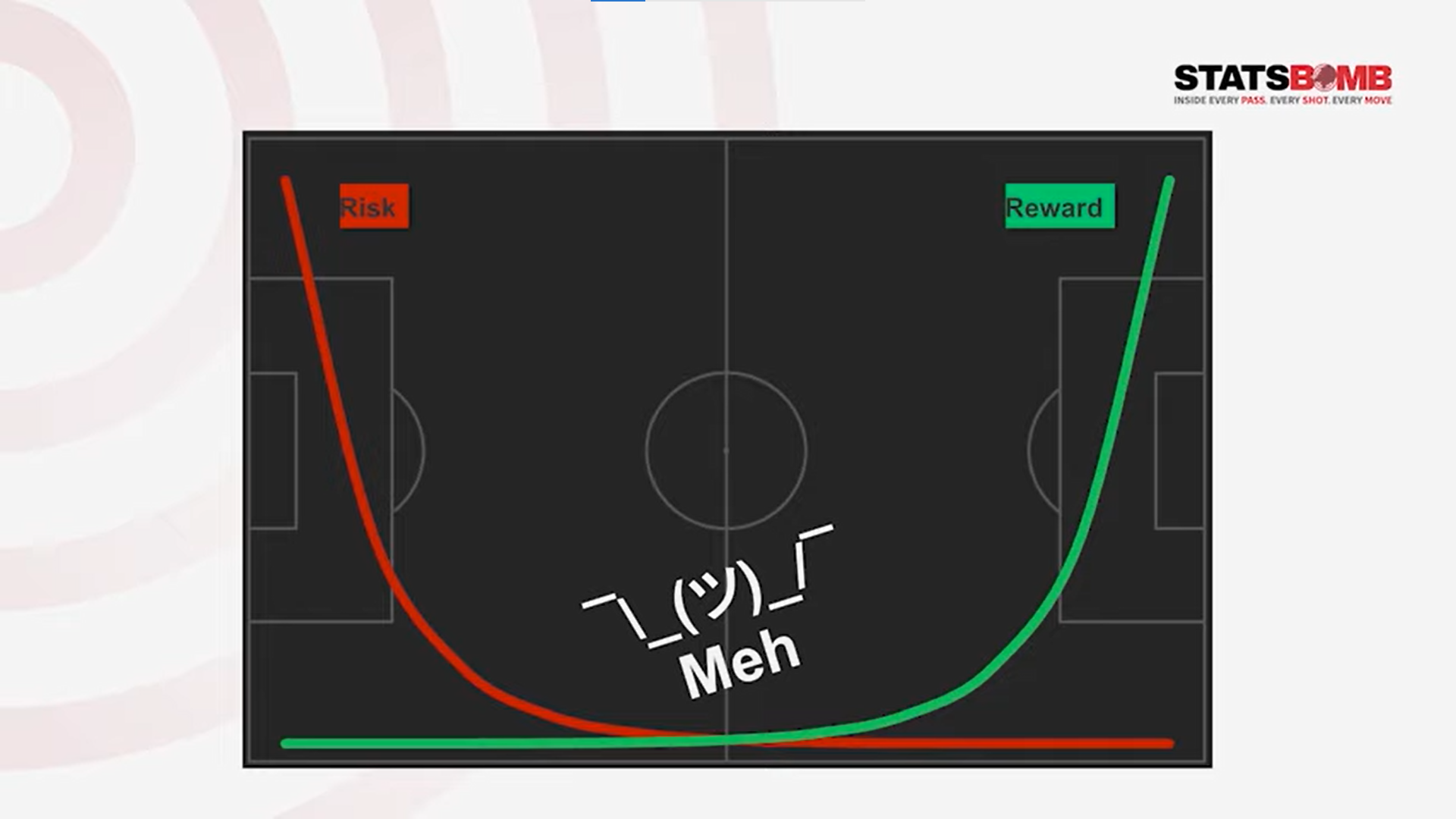

Anyway. The pause of Guardiola's players on the ball in inconsequential areas links to one of my favourite phrases in football analytics. In a 2019 talk at the inaugural StatsBomb analytics conference, Thom Lawrence used the phrase 'trough of meh' to describe how there's a big area in midfield that is far removed from the risk or reward opportunities close to goal that statistical models pick up on.

The fun thing about the trough of meh, beyond pure linguistic frivolity, is that we know the name is only accurate when talking about models. We know that midfield is important in football (fifty million Guardiola brain cells can't be wrong), we just haven't found the numbers for it yet.

It's time to talk about time.

Most possession value models (they do what they sound like they do) base the impact of a particular event on how it changes the chance of scoring or conceding in the next X seconds or phases of play. This makes sense if you're interested in the impact of the action - it'd be silly to credit a pass twenty minutes ago as playing a part in a goal that was just scored. But it does sorta assume that football gameplay incentives are the same as basketball's. And football isn't basketball, it's a completely different sport.

Or, it sometimes is. The point made by Lawrence's 'trough of meh' slide is that your chances of scoring a goal increase very steeply as you approach the posts, with the same thing (as a risk of conceding) happening at the other end. What if this intensity of value in certain parts of the pitch, and the tantalising possibility of getting to it when close by, essentially eliminates the any clock-based incentive when in that part of the field? Although there could be 45 minutes' worth of unbroken play possible, if the ball is near your goal then you want it gone now. Similarly, if you're a step away from generating a, say, 0.5xG chance then it'd be silly to say 'well, we have an hour left'.

Neither of these sentiments is true for midfield though; it doesn't have the implicit 'shot clock'-like qualities that the areas near the goals have. If you want a cricketing metaphor - and why wouldn't you - the parts of the pitch close to goal are a T20; the midfield is a Test match.

In the hope that each repetition of this point will be more finessed than the last, I think this is why possession value models struggle with the midfield. The models' in-built time limitations happen to align with the realistic definitional aim of the game at either extremity of the pitch, but don't align with the the realistic definitional aim of the game in the middle.

Eureka.

Sadly, what is still to be eureked is what is valuable in midfield.

I think it would be fair to say that, as many current coaches appear to believe, control of the ball is a significant aim, and the middle of the pitch is a better place to do that than hear your own goal. The fact that your opponent will usually have the same belief means that maintaining control in itself will be a genuine challenge.

I also suspect that part of the reason why teams don't simply spend the ten minutes before half-time passing the ball near the centre-circle is psychological. You'll quite often see teams get a little bit lax when they're 'just' recycling the ball, and mental errors creeping in can often let the opposition in on goal as well. Perhaps, despite the 90-minute shot clock, there's an 'internal' limit to how long teams can keep the ball in midfield.

If all this is true then part of the value in midfield could be something like 'maintaining the capacity to attack', rather than necessarily 'to attack'. This aligns with a phrase of @TiotalFootball's which has stuck with me since I read it, of 'building capacity'.

it's about moving around as a team, and moving the ball around as a team to build the capacity to successfully move the ball into the penalty area before your opponent does

— Tiotal Football (@TiotalFootball) September 13, 2021

I prefer this as a concept to the common 'building through the thirds' which, to me, feels too sequential, too much like a step of Lego instructions. 'First build the base. Turn the base around; you've reached the middle third. Now build the Millennium Falcon walls; you've now reached the final third. Now build the Falcon's roof; attach it. You've now scored a goal'.

I don't know how you measure this though - if the aim of midfield is to build and maintain a capacity to attack, a potential, then what numbers do you attach to that?

In the hopes of helping, I have what is probably an incorrect but possibly useful oversimplification: is midfield possession simply about wasting the time that your opponent can score in while retaining the potential to score yourself?

Is the point of midfield possession primarily just... timewasting?

If it is, I'm sure Archimedes would have enjoyed the modern, midfield-possession era of football. Wasting time with the slim chance of divine inspiration, it sounds just like his bathtime.

Notes

The main body of this newsletter captures a pretty complete, neatly-packaged set of thoughts, but I wanted to collect some stragglers here which would've disrupted the train of thought if I'd included them above.

The first is that I have a nagging memory of seeing some kind of possession value with a time or score effects feature factored into it before. There are so many different sources touching on this that I didn't find it in some quick checks. It might be a fake memory, but I want to acknowledge that this idea might seem new to me purely through forgetting or being ignorant of other work.

Another important point is that, even if this 'theory of midfield' works for modern-day elite football, I feel like there's a chance that it - and certainly implimentation of it - could be too focused on that level of the game. At other levels, and in other times past and future, the short-term goal value of areas of the field might be different, or the steepness of the value curve might change.

Footballing differences applies not just to chance creation but to maintaining possession as well. That thought I threw out there about a psychological limit to the length of time teams can hold onto the ball but change, making long passages of keep-ball more likely.

I think that this area of thought marries up with the concept of 'defensive possession', maybe even 'rest defence' too, where your structure in-possession has to be considering how you'll be defending when you eventually inevitably lose the ball. They're both tactical theoretical approaches that consider possession as more than merely a means to an end of scoring a goal.

I don't know a lot about player fitness but I also suspect that the slower tempo that midfield possession offers is part of what allows footballers to keep performing for the whole match. That seems like something that would make modelling very difficult: what if a midfielder is effective because they can help control possession for long enough for their attackers to rest, mentally and physically, for a little bit?

Finally, it's difficult to credit the things that have been a background influence to an idea but, as well as the things mentioned in the main body, there are some things that deserve a mention.

One is Van Haaren, Rahimian, Abzhanova, and Toka's paper on a reinforcement learning model for player decision-making, which used different reward functions for different phases of play. Another is Ted Knutson's [once tweeted/podcasted, echoed in the book Net Gains by Euan Dewar] opinion that set-piece efficacy stats were so bad because teams didn't train for them; that the sample was essentially misleading. And another is an article that I think I read a few years ago about the factor of time in T20 innings, possibly this one by Jarrod Kimber, arguing that teams were leaving runs on the table by being too cautious of getting out.

Final final note: I started drafting this the day before the T20 final. Ended it just after the final ended. Congrats England. You justified the amount of cricket written into this football analytics newsletter.